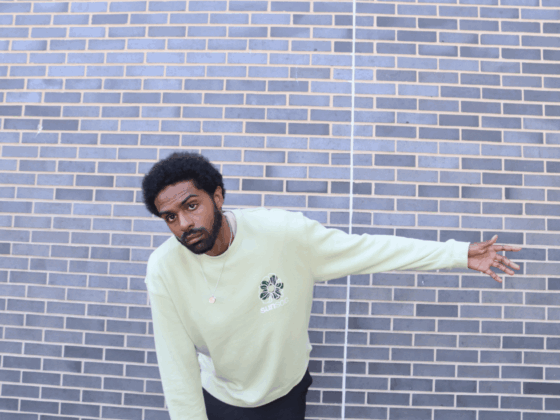

Shoka Sunflower unpacks emotional avoidance on "Two Step"

Johannesburg-based artist Shoka Sunflower marks the beginning of a new refined and deliberate chapter with his new single “Two Step,” in collaboration with genre-blurring producer Moo Latte. Built on breezy…

Share